Preface

This is an input of the URBACT III Boosting Social Innovation Network into the Pan- European discussion on cities and social innovation.

It is planned as a support for any city administration, however small or large, wanting to focus on and develop social innovation.

This is not window dressing but a real evolution towards a co-created city.

Choose your chapters at will, you don’t have to read everything. This text is charged with links if you want to go further.

If you are just starting go to the Booster chapter, if you are already a fertile ground for innovators go to the Ecosystems chapter

and if you want to get into impact measurement try the measurement chapter. Happy reading!

Fabio Sgaragli:

The importance of social innovation lies mostly in the underlying assumption that the current model of social development is undergoing a massive crisis, both in terms of its sustainability and its capacity to deliver sense and equal prosperity to all. Social innovation represents a new and specific process for innovation through which alternative models of social development can be invented, prototyped, tested and scaled. The mission of social innovation is therefore to help us find a novel and shared ecosystem of interactions and interrelations based on an integrated approach to development, one that takes into account the economic, social and environmental dimensions.

In the context of the many papers, publications and final project reports on the fashionable topic of social innovation, the Boostinno project’s final report “Wellbeing in cities: a social innovation revolution” is a welcome novelty.

Written as a smart guide for cities wanting to either start or grow a local ecosystem for social innovation, this online document is an easy-to-read manual with a variety of insights, examples and external references that make it useful and practical at the same time.

This is an input of the URBACT III Boosting Social Innovation Network into the Pan- European discussion on cities and social innovation.

It is planned as a support for any city administration, however small or large, wanting to focus on and develop social innovation.

This is not window dressing but a real evolution towards a co-created city.

Choose your chapters at will, you don’t have to read everything. This text is charged with links if you want to go further.

If you are just starting go to the Booster chapter, if you are already a fertile ground for innovators go to the Ecosystems chapter

and if you want to get into impact measurement try the measurement chapter. Happy reading!

Fabio Sgaragli:

The importance of social innovation lies mostly in the underlying assumption that the current model of social development is undergoing a massive crisis, both in terms of its sustainability and its capacity to deliver sense and equal prosperity to all. Social innovation represents a new and specific process for innovation through which alternative models of social development can be invented, prototyped, tested and scaled. The mission of social innovation is therefore to help us find a novel and shared ecosystem of interactions and interrelations based on an integrated approach to development, one that takes into account the economic, social and environmental dimensions.

In the context of the many papers, publications and final project reports on the fashionable topic of social innovation, the Boostinno project’s final report “Wellbeing in cities: a social innovation revolution” is a welcome novelty.

Written as a smart guide for cities wanting to either start or grow a local ecosystem for social innovation, this online document is an easy-to-read manual with a variety of insights, examples and external references that make it useful and practical at the same time.

0

INTRO

The URBACT "Boosting Social Innovation" network was co-constructed by 10 very large and medium cities (Braga (PO), Baia Mare (RO), Barcelona (ES), Gdansk (PL), Milan (IT), Paris (FR), Strasbourg (City and Europmetropole) (FR), Skane County (SE), Turin (IT), Wroclaw (PL)). Through the work done over three years, these cities have found, that social innovation is not just a trend, but could be qualified as a fundamental change in the management of cities, in the management of impact and in the relations cities uphold and develop with their inhabitants. Some would describe this change as equivalent to the industrial (steam and electricity) or the IT revolutions of the XXth and XXIth centuries.

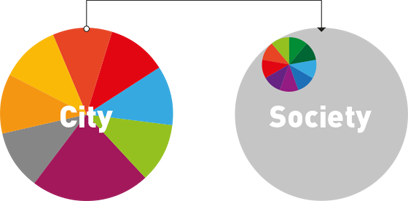

Up until now, one of the basic assumptions of urban policy, was that the citizen will accept what is decided, planned and built. Recent years have shown that it is often the citizens who are the makers of the city, organising themselves, as says Manzini, in a collaborative perspective. Where this does not happen sufficiently, we are in a situation of social and often economic relegation and cities discover that they have whole areas at their doorstep which they have to regenerate. This is not just a territorial phenomenon, but one which touches the whole of our societies, because as G. Mulgan underlines, the redistribution of wealth, notwithstanding our collective hopes, has not happened, even due to the IT industry, which has mainly remained a closed bubble and has enriched only those who have managed to participate.

We would therefore like to propose a vision of the reality of 2018 on which the Living Lab of ten cities has worked very hard and which they want to continue as an ongoing process.

Social innovation in practice:

As Mayor, politician, director of strategic development, economist, social worker do I need social innovation and what will my territory get out of it?

We will try to answer this question in this innovative report, by describing a certain number of our experiences, which fully show how and why the above very simplified theories of our researchers, are confirmed in reality.

0. The overriding human factor.

Citizens and civil servants and politicians as well as entrepreneurs, academics and activists are all human beings!

This unsurprising knowledge is largely ignored by most projects, strategies and operational programmes. However in the Boosting Social Innovation network we emphasize that without building, reinforcing and understanding the importance of human relations nothing can be achieved. Within the network it was only when the participants got to know each other that they started to really interact, to exchange and to work on a priori trust. The analysis of their structures shows that this aspect of co-construction and co-decision is central to the success of cities going forward and has a slowing down effect where it does not exist. This was strongly emphasised by the work done on the quality of relations through the sense mapping process.

In the ten partner cities there are many spaces dedicated to start-ups. Only in one of these spaces is there room for public servants. They need creativity as much as anyone in the private sector and these internal social innovations can really improve the way they work, think and succeed. These examples may seem unattainable to many, but they are full of surprises, as creativity and experimentation is not something which is simple to have and can almost not be bought; but it allows "institutional entrepreneurs", as some call them, to develop social innovation within and around city halls as is shown in Turin’s new transfer network on this subject.

Managing social innovation in municipal structures requires spreading to all departments and has to irradiate all levels of the decision making processes. This will empower those civil servants who are closest to the inhabitants, to experiment and allow them to fail in certain circumstances. This acceptance of failure should be worked out whilst identifying and sharing a theory of change, which has to include the idea that an innovation can be very original, but may not work, is not accepted or may cause too much disruption in other sectors.

1. Working with everybody - being a broker

A local authority was often the decider on many questions, based on the representative democracy that we all know and cherish. But we also know, that sometimes, well thought through decisions are refused by citizens, because of a lack of co-construction, co-ownership. In other words a lack of respect for their opinions. In Boosting Social Innovation we have been inspired by the "Quadruple helix", which invites us to share the development of our territories not only between the private and public sectors and with the knowledge sector but also with citizens, not as experimental testers of policy, but as co-authors and sometimes inventors of solutions.

Quadruple Helix Innovation

Government, Academia, Industry and Citizens collaborating together to drive structural chanfes far beyond the scope

of any one organization could achieve on it’s own

Involve all stakeholders in quadruple helix to innovate and experiment in real world settings, in creating frictionless ecosystems

Government, Academia, Industry and Citizens collaborating together to drive structural chanfes far beyond the scope

of any one organization could achieve on it’s own

Involve all stakeholders in quadruple helix to innovate and experiment in real world settings, in creating frictionless ecosystems

The knowledge sector can help a lot, bringing in the importance of design, market analysis, which should permit an easier decision making process. As states Manzini, the citizens are making the city from inside themselves.

The new role for public institutions, and especially local authorities fits in well to that of a broker. Each person, each department, the city hall as an administration and its partners have to move from a secure traditional ruling role, to a more convivial, uncertain, smaller comfort zone of a broker, who deals out the cards to different stakeholders, creating the potential for them to be coherent and to work together for the common good, creating commons and wellbeing in the community.

2. Booster.

If a public institution wants to develop social innovation, it has to act as a booster. This implies, on the basis of the experience of the network, creating spaces accessible to new projects as in Paris, cross fertilising experiences and ideas as in Gdansk, creating ecosystems and then adapting them to the evolving situation of Turin or influencing mainstream policy through such experimentations as civic crowdfunding in Milan. The process of boosting social innovation was very varied in the network's cities; some were very refined, others were just being created and in some cases it was just the beginning. Every city can start this process.

3. Knowing what we are doing.

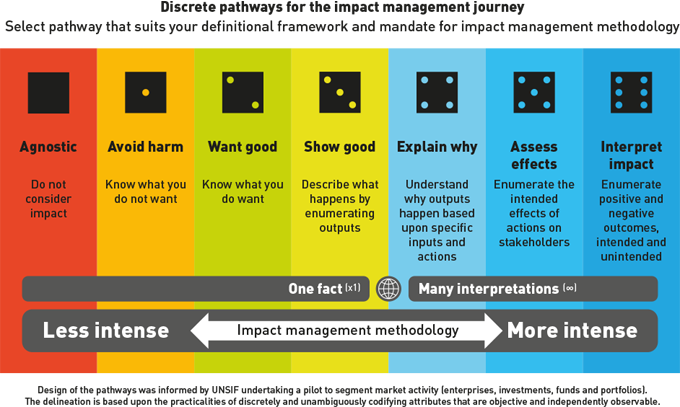

Many EU documents make reference to evaluation, impact measurement etc. In reality many cities do not have the real capacities to measure what they do and they continue to take decisions on the basis of impressions, political impulse or intuition. This network of large and medium sized cities thinks, that it is time to be able to base decisions on evidence. This process, accompanied by the specialist of impact from the UNDP SDG Impact Finance (UNSIF) Karl Richter, has evolved from impact measurement to impact management, putting the emphasis on knowing what we want to measure and on the process of decision making, which is a consequence of this knowledge.

4. From people to efficiency.

The Boosting Social Innovation cities think that social innovation is growing into a social revolution, based on the most positive aspect of human beings. Appreciating this and engaging it for the common good is the challenge the cities gave each other in Paris by signing the co-constructed "Call for action". We hope as cities that you will join us in this new exploration of the human kind, the 4th Industrial Revolution.

1

CITY CHALLENGES

Urban challenges are well defined at European level and they constitute the EU Urban Agenda. They are common for all cities, independently of their size or geographical location.

Most of the 12 themes of the Urban Agenda are absolutely central to the work done in the Boosting Social Innovation network and constitute the reason to get involved in social innovation which produces multiple, integrated solutions.

Below you will find examples of urban actions of the 10 network cities, which show the importance of social innovation in urban policies. These examples do not represent a complete picture of the work done by these cities but are included to try to illustrate the importance of social innovation in urban policies today.

2

THE CITY AUTHORITIES AS A BOOSTER

How to start?

All communities face smaller and bigger social challenges, depending of where we live. Boosting social innovation is not the monopoly of city administrations, as many stakeholders (the private sector, the knowledge sector and citizens) can do it as well. The social innovation approach is based on the idea that one actor (e.g. a municipality) is unable to perform all the roles, which are necessary to address the challenges. It is impossible to take responsibility for naming the challenge, finding and funding the solution, finally testing and scaling it. It is much more feasible to make a change if the different stakeholders share their assets. The experience of the Boostinno network has shown that local authorities have a key role to play in creating the right conditions for the internal development of the city, by stimulating social innovation. We hope that these questions and answers will help you to start, or to improve what is happening in your city: to become a booster...

3

BROKERAGE

Real exchange is hard to achieve: need for brokerage

The whole innovation discourse is teaching us that we have to think and operate differently on all levels. Lessons learned from the Boostinno project confirm the theoretical assumption that collaboration is the pillar of the societal order, which is the only way to deal with the complex challenges we are facing now.

The second step of collaboration is actual exchange - of ideas, assets, commodities, ways of thinking. And at the top of that we have sharing.

Local authorities are confronted today with such phenomenon as "big data", "big picture", urban activists, ecological defenders of all changes, lack of finance. Inhabitants are faced with ununderstandable institutional language, decisions they don't understand and a feeling that they have no influence on anything. This vision appears to be even stronger in the so-called regeneration areas, often ”forgotten” by the city authorities.

This strong tension can be resumed by the lack of connection between the top down and the bottom up approaches, The Boosting Social Innovation network has identified, with the help of the SIAC Network the idea of brokerage. Some cities have found in this idea a new way, level and methodology of building real exchange between city authorities and citizens. Indeed "city and citizens" together with the "governance and policy making" themes constituted part of the backbone of the Boostinno network.

In short the brokerage function changes the relationship between city authorities and their citizens, by changing the way in which they collaborate. As indicates prof. Manzini, it is the citizens who are for a large part building the cities from the inside. This is confirmed by the way in which municipalities are trying to reach communities in more difficult areas of their cities. This is also based on the conviction that no city can develop well leaving behind part of its population, which in some cities has really lost contact with the rest.

If the brokerage function develops to become the basis for intensive collaboration between the city and it's citizens suddenly sharing, co-decision making, co-living values, short production circuits, social and solidarity economy or circular economy become the subject of the day, as they are really what citizens are concerned by, but may need more leverage and understanding from the city government, to be able to activate their ideas and actions.

In this sense brokerage becomes sensemaking, stimulating the sharing of values, commodities and assets. At the same time brokerage gives a new dimension to the relationship building question as the process of building relations and knowing who is working on what and what added value this can give is central to good governance and of course the impact measurement and management of local, regional or even national and EU policies. What can brokerage mean on the daily basis?

- habitat of shared experiences – openness for inviting people from different social classes, backgrounds and professions to think and act together (co-creation of policies),

- mediation or mediator which/who enables connections, understanding and collaborations, e.g. joint workshop for people from different sectors where they can freely explain their perspective,

- trying to link people, institutions, organisations and groups of citizens who can be useful for each other,

- sharing your data, knowledge, challenges and questions - being open for engagement of those whom you never work with,

- taking care of constant communication

- translation of different approaches, worldviews and practices to enable balanced collaboration

- fostering connections which enable real change and actions (integrated urban development management)

- sharing of responsibilities and wellbeing.

Examples:

Gdansk: the Integrated Action Plan was conceived, designed and created by a group of local innovators, coming from the city administration, NGO's, the private sector and the knowledge sector. A "broker" was brought in to help make sense of the work of the group and to propose a final version, which the group sifted through and accepted.

Baia Mare: the project coordinator found himself managing several local groups after the visit of the lead expert. This produced unplanned energies and allowed the new relationships between the city authorities and the citizens to flourish, creating a very innovative brokerage relationship.

Practicalities:

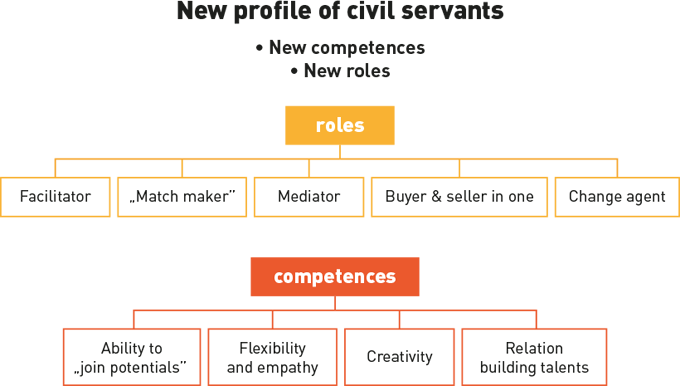

Being a broker, for a civil servant, a politician, a city administration implies a new form of governance, new profiles for civil servants and the capacity and will to build up new forms of relations. For the Boosting Social Innovation network cities this means, that co-creation is the only way of policy making, management should be based on integrated urban development, policy implementation should be based on partnerships and partenerial relations, which come out of networking and process facilitation. Only such functioning will empower citizens, who become creative empathetic partners, and permits the creation of added values.

The roles and competences of civil servants and even politicians are quite different from the traditional ones, and this implies a lot of changes in the internal management of cities, as more and more of our collaborators have to be “out of the office”. This gives specific content to the new “social innovation paradigm” where relations are based on trust and respect, people function on the equal partner footing, each civil servant tries to approach her/his partner with an individual approach and networking stands as the basis for success, as it will oblige the municipal systems to work across silos, in an integrated, inclusive and open fashion.

The only question which we have to ask ourselves is “are we ready”? WE that means city authorities, citizens, entrepreneurs, academics, civic organisations, NGO’s, city movements, informal groups. Are WE ready to share responsibilities and wellness, are we ready to work for the common good, are we really ready to be truly innovative?

4

ECOSYSTEM(S)

How we should think about the city to help it effectively face its challenges and develop smart usage of its assets? Which metaphor can embrace all the complexity we are coming across while thinking about introducing change? Which notion can support us in navigating between all those informations, theories, good practices and recommendations?

Cities are the result of a collective intelligence allowing different initiatives, groups, businesses and cultural events to co-exist, thereby creating a collaborative city. However these energies[1] need to somehow be linked into the general functioning of a city. Rules and regulations can be produced in a Cartesian fashion, and become a system. However an eco-system does not respect the same rules. It is selfcreating and does not follow a determined path, but rather tries to create new realities, often in social innovation. It may continue or it may stop. It may be more or less creative.

In every city there is more than one eco-system and, as underlines Manzini, the result is ungovernable and messy but is strongly enabling. It is exactly this lack of predictability and the strength of the improvisation and innovation that make eco-systems so important to the cities of today. A city should therefore not try to manage the eco-systems, because as Turin found out, it is better to be one of the members of the eco-systems, than to try to be above them. The creativity of eco-systems appears to increase in proportion to their freedom and autonomy.

Eco-systems can however be supported in different ways: calls for ideas, spaces (Braga Gnration, Gdansk social hub, etc), co-construction methods (Strasbourg – co-construction of social innovation policy, Start up de territoires), participative budgets (Baia Mare). It is really the brokerage role of the local authority which here comes into force, as the mediator and host of the city, who invites the citizens to fill out the real meaning and content of the city.

Obviously not everything can come from the inhabitants, but many complicated situations can be alleviated, through a strong brokerage role, especially if it is shared between civil servants and politicians, as well as other partners of the city. This is even more so in difficult areas, where for numerous reasons the role of the city administration has diminished to almost nothing. Notwithstanding it would appear that many cities such as Barcelona or Milan are working on a return to these areas in need of regeneration, and are using local mediators, local municipal offices and other means to get closer to the inhabitant and build up the capacity for dialogue. This in turn allows the city to pursue more innovative policies in areas such as urban mobility or the circular economy, which cannot achieve success without the participation of the local population.

In short the main makers of a city are it's citizens, who organize themselves in various ways. It is therefore the responsibility of the city to enable these self creating eco-systems to exist and thrive. As we have seen they cannot "be organised" as they are too complex and their development cannot be foreseen. However producing virtual and real spaces for them is vital. Measuring their social and financial impact is the next collective challenge, which we are all facing.

[1] It is almost surprising that in none of the network cities was there a "department of energy" (the human one) which underlines the importance of the human touch, which is taken so much for granted, but is hardly managed at all.

Co-visualizing the in-between

Social innovation is about addressing very complex "wicked" problems, in which actors from across many sectors - governments, corporations, educational institutes, NGOs, and, of course, citizens - need to work together intensively for a prolonged period of time. In this way, deep lessons learnt can be shared, and collaborations can come to fruition that align and scale efforts beyond the prototype and project level so as to reach truly collective, integrated and systemic impact. To collaborate successfully, participants need to be able to recognise not only the various interests and perspectives of all stakeholders involved, but also to see the evolving "big picture" of the quality of (potential) connections within all that diversity.

Building this shared understanding is already difficult at the level of a city, when people representing different communities can often meet face-to-face. It is even harder at the national, let alone the European level. The core problem is the fragmentation of collaboration that happens when addressing an intricate web of wicked problems. This requires countless participants to work together, often for a very long duration, and on an array of interrelated solutions. This fragmentation is compounded by everything continuously being in flux: the shifting articulations of the problems, the multitude of approaches, the many stakeholders involved as well as resources available, and so on. Thus, fragmentation of collaboration often results in confusion, the reinventing of many wheels, and only suboptimal solutions. Mapping can help reduce this fragmentation.

Maps are powerful visual artefacts to help people navigate complex spaces. We all know location-based maps that help us navigate from A to B. This geographical metaphor has been extended to create online maps of location-based social innovation services and resources, such as the Paris map where we can see the location of hundreds of “actors” within the social and solidarity economy. These location-based maps are good at classifying and positioning elements, but less suited for capturing their network of collaborative relations.

Another type of map is the community network map. These do not start from a geographical metaphor to provide the necessary reference points, but instead use salient commonalities of the community network itself, such as the issues, goals, themes, or the “sharings” that their collaboration is about. Such maps provide joint conceptual beacons that help participants and others to explore and navigate their often very complex collaboration space. Typically, social network analysis maps capture some such relations, but in a formal, analytical way. An example is the analysis of the Torino informal startup network. Using full-fledged community network maps, however, their members can interact with the map and see how their goals, themes, activities, organisations, stakeholders and resources interrelate. Participants can perceive how they themselves are positioned in this collaboration landscape; where they might want to take their contribution from there; and visually anchor their own efforts in the collaborative network. In short, this type of mapping both shows and grows the network of collaborative relations, on which the creativity of social innovation depends.

5

IMPACT MEASUREMENT

Management of impact is an evolving concept. It became the fourth main heading of the Boostinno network, as cities concluded that knowing what the impact of the work on social innovation is is key to obtaining political support for such actions, as well as recognition by society at large. We joined the SDG work through the director of Knowledge and Research of the UNDP SDG Impact Finance (UNSIF) Karl Richter, who allowed us to appreciate the complexity of measurement, to clarify concepts and to realize that the intensity of the measurement and management depends on the local territory, its needs and possibilities.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the United Nations benefit from a planetary effort to improve the way in which measurement and evidence based decisions can become everyday elements of decision making and appears to be central to the thinking of the Commission in it’s planning of the next 7 year budgetary period. This global trend shows, that at the present moment there is a move from underlining the importance of impact measurement, to treating the question of impact management as central. This would allow more insistence on “why” something happens and less on “what” happens, which in turn allows easier decision making and empowers all the stakeholders to choose which elements require the most effort concerning their impact.

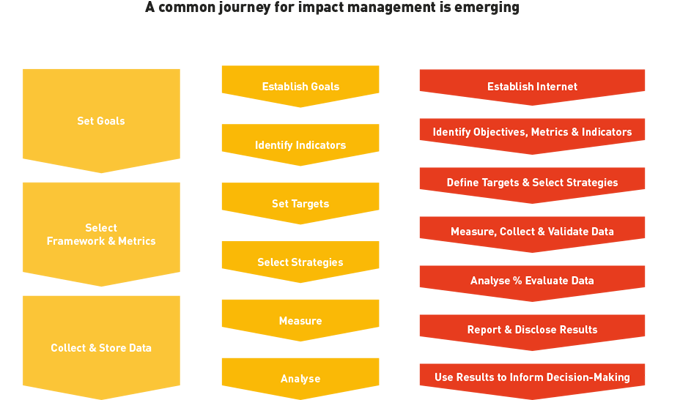

In order to be able to at least slightly harmonise impact management there are three axes to be taken into consideration:

1. a common journey,

2. different pathways for making that journey,

3. varying levels of intensity of the evidence required.

Historically in the last 20 years approaches to these axes have evolved very rapidly to achieve in 2018 the following shape:

However the process of impact management is not simple. Even if there is overall agreement on the above stages of the journey, several variables now come into play. Firstly from what perspective are we looking, secondly who is the institution or person and what are the most important interests, thirdly what is the intensity which is required to get a qualitative result.

To take into account that the whole sphere of impact management is dependant on the following formula:

As can be seen such a variety of pathways should satisfy most public authorities and allow them to pursue the impact management at the level of their needs and means. This choice also lets the public authorities realise how many pathways are available and opens the door for different choices at a further stage.

In the case of the SDG’s Karl Richter proposes elements, which allow comparison, assurance of quality, interoperability and resource allocation.

Choosing the level is a question of perspective, context, financing capabilities, reasons for needing the assessment of the impact and the rigour of data required.

6

CONCLUSIONS

Our civilisations and planet have in the last few hundred years gone through 3 previous revolutions:

- steam,

- electricity,

- electronics.

- the producer and consumer are no longer separate entities and often become "prosumers",

- the frontiers between the world of work and the rest of our lives have become very fluid, and help this "prosumer" paradigm to develop,

- the eco-systems which are present and the prosumer paradigm necessitate very agile management, both in the private and the public sectors, moving away from the "we decide once and for all" towards permanent creative management,

- the development of social innovations in the private, III sector and in the public one results very often in tailor made products, services and partnerships,

- all this complexity demands forms of "open management" which put pressure especially on public authorities, to be reactive, creative and to be able to adapt to changes as quickly as they come about.

To conclude, social innovation as the new revolution strains the older systems of working and governance, but could be an answer in relation to the extremes that European countries are witnessing, as it drives citizens energies differently. It also relates directly to values, moral ones and market ones, bringing them together to try to produce a collective transformative wellbeing.

Boostinos`s 10 encouragements for public support of social innovation

1. Public authorities must learn to know how to balance between inside city citizen initiatives and energies and their own planning systems.

2. Approaching the inhabitants as a fertile ground, where needs are known and solutions can be invented is the key for fostering social innovations.

3. Understanding that a new revolution is taking place in the city "market place": social innovation is as important a change as steam, electricity or IT and brings in and develops added social value.

4. Public authorities have to start with themselves: what social innovations can help their own functioning, what changes can be installed?

5. Change is a personal phenomenon: as a civil servant can I change my office into a creative meeting place? Can I allow my co-civil servants to "float" on creativity and inventivity to get the best out of them?

6. Building up eco-systems of social innovators is their challenge. The public sector has to foster this development, facilitate, co-create spaces, eliminate difficulties and link different families of innovators.

7. Accepting a theory of change in a public body, will empower it to appreciate the permanently transformative normality of social innovation, much of which, if it proves itself, must just become the new normality in the end.

8. Knowing what we are doing and what the results are. Impact measurement thinking is moving from measurement itself to impact management, meaning moving from counting "what" to understanding "why" allowing decisions to be taken as to what it is relevant to measure and create the indicators to do so.

9. Social innovation produces change, but requires the recognition of failure, as it is based on experimentation. The capacity to fail must become included in public procurement, in EU subsidies and other forms of financing, so that social innovation has the space to thrive.

10. Responding to this new social innovation revolution public bodies have to review their vocation and system of functioning. They are no longer the rowers in the boat, nor even the helmsman, but more likely the recruiters of future sailors, who should not use press ganging[1] methods. In this way they become true brokers of social innovation.

[1] press gang: group of sailors from ships who in ancient times would take young men by force, to become sailors of navy ships in the UK.

7

ANNEXE

The culture of experimentation

based on NESTA

Reflection 1: Experimentation as a way of accelerating learning and exploring “the room of the non-obvious”

Governments need to increase:

- their pace

- their agility

- in learning about which ideas have the highest potential value-creation

- and make people’s lives the rationale of governing.

Reflection 2: Experimentation as a way of turning uncertainty into risk

- run your experiments at an early stage,

- reduce risk due to small budget and available resources,

- learn from your mistakes,

- therefore closing the gap between uncertainty and risk.

Reflection 3: Experimentation as a way to reframe failure

- Bad failures can be considered as preventable failures in predictable operations.

- Good failures, are often unavoidable failures in complex systems or when entering uncharted territory and dealing with high levels of uncertainty.

- In practice, ideas are never fully formed, but need to work in and adapt to a dynamic system

Reflection 4: Experimentation on a continuum between exploration and validation

Reflection 5: Experimentation as cultural change

- Mindset – fundamental set of assumptions and perspectives that frame the understanding of one’s own role, practice and potential.

- Attitude – emotional state that creates a propensity to perceive and solve problems in a particular way.

- Habits – fundamental actions and activities that one views as essential and valuable in exercising one’s professional role.

- Functions – core operational tasks of government (i.e. how to approach policy development, procurement, etc.) that often go unquestioned.

- Environment – factors and elements that shape how decisions are made and how development processes are enabled and authorised.

8

CREDITS

Many thanks to all the participants of the Boosting Social Innovation network. But as we want every reader to become a participant in building social innovation, we include a list of participants, their email addresses and a word on their competences or special interests, to incite the reader to make contact:

Baia Mare (Romania):

Dorin Miclaus: miclaus.dorin@gmail.com - bottom up participative co-construction going towards brokerage

as a new form of governance.

Barcelona (Spain):

Cristina Gil-Adelantado cristina.gil@barcelonactiva.cat - international relations, social innovation in peripheral areas.

Barcelona (Spain):

Cinta Arasa Carot: cinta.arasa@barcelonactiva.cat - international relations, social innovation in peripheral areas.

Braga (Portugal):

Carlos de Sousa Santos: carlos.santos@gnration.pt - 100% Youth Policy, Erasmus trainer, city center reoccupied by youth, multifunctional social innovation centre.

Braga (Portugal):

Eva Sousa: eva.sousa@cm-braga.pt - municipal specialist in youth policies.

Braga (Portugal):

Cristina Palhares: cristina.palhares@cm-braga.pt - assistant to the mayor and the deputy mayor.

Gdansk (Poland):

Magdalena Skiba: magdalena.skiba@gdansk.gda.pl - project coordinator, head of innovation and partnership unit in Gdansk city hall.

Gdansk (Poland):

Magdalena Zawodny-Barabanow: urbact@gdansk.gda.pl - co-coordinator of Boosting Social Innovation.

Gdansk (Poland):

Michał Pielechowski: michal.pielechowski@gdansk.gda.pl - the ideal new younger civil servant.

Milan (Italy):

Renato Galliano: renato.galliano@commune.milano.it - director of economic development, creator of alternative financial instruments.

Milan (Italy):

Annibale d’Elia: Annibale.DElia@comune.milano.it - director of economic innovation, exciting speaker, explains the 4th industrial revolution.

Milan (Italy):

Clara Callegaris: Claramaddalena.Callegaris@comune.milano.it - Head of Smart City unit.

Milan (Italy):

Anna Cristina Siragusa: Annacristina.Siragusa@comune.milano.it - civic crowdfunding.

Paris (France):

Patrick Trannoy: patrick.trannoy@paris.fr - responsible for development of social, solidarity economy and Head of circular economy office.

Skane (Sweden):

Jorgen Dehlin: jorgen.dehlin@lansstyrelsen.se - social innovation and culture.

Strasbourg (France):

Sandra Guilmin: Sandra.GUILMIN@strasbourg.eu - responsible for social and solidarity economy development - specializes in co-construction and co-management.

Strasbourg (France):

Agathe BINNERT: abinnert@maisonemploi-strasbourg.org - deputy director Job Centre.

Strasbourg (France):

Manon MARQUIS: m.marquis@cress-grandest.org - Regional Chamber of Social and Solidarity Economy.

Strasbourg (France):

Agnès GUTH: direction@regiedesecrivains.com - director of a social entreprise « Régie des écrivains ».

Strasbourg (France):

Stève DUCHENE: sduchene@alsaceactive.fr - Alsace Active – alternative sources of financing.

Strasbourg (France):

Delphine KRIEGER: delphine.krieger@strasbourg.eu - responsible for Innovation at Eurométropole de Strasbourg.

Strasbourg (France):

Marion BARDOT: Marion.BARDOT@grandest.fr - Regional Council.

Strasbourg (France):

Pauline SCHELL: pauline.schell@sielbleu.org - association SIel bleu.

Strasbourg (France):

Eric LEGALL: e.legall@alsaceinnovation.eu - « Alsace innovation » agency.

Strasbourg (France):

Sophie KELLER: skeller@lelabo-partenariats.org - Start up de territoire.

Turin (Italy):

Fabrizio Barbiero: fabrizio.barbiero@comune.torino.it - responsible for social innovation and the changes in it’s management, brilliant speaker, super networker.

Turin (Italy):

Nadia Bonghi: nadia.bonghi@comune.torino.it - receives and supports all social innovation projects.

Wrocław (Poland):

Małgorzata Golak: Malgorzata.Golak@um.wroc.pl - regeneration of a main street, participation with different stakeholders.

Wrocław (Poland):

Marzena Horak: marzena.horak@um.wroc.pl - deputy director of infrastructure and economic development.

Authors:

Piotr Wołkowinski, lead expert, Boosting Social Innovation, with the support of Aleksandra Gołdys,

Michał Pielechowski, Magdalena Skiba and Monika Chabior and with the collaboration of Fabio Sgaragli, Aldo de Moor and Karl Richter.